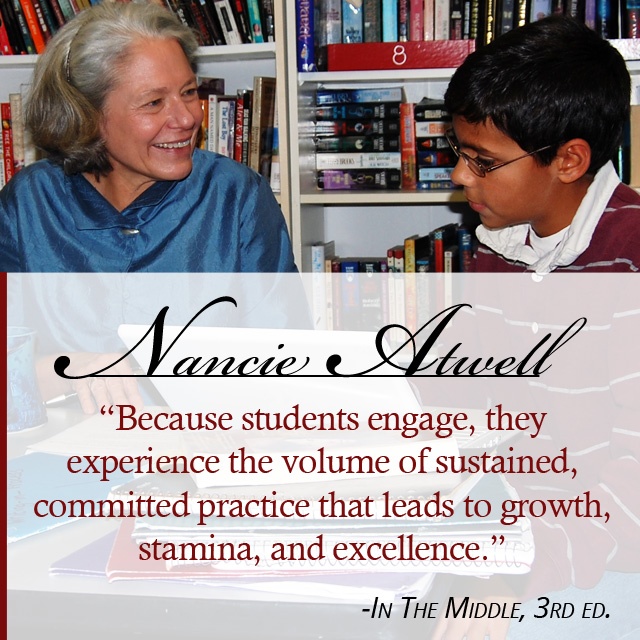

With our In The Middle Wednesday series, Nancie Atwell discusses how becoming a parent influenced In the Middle.

With our In The Middle Wednesday series, Nancie Atwell discusses how becoming a parent influenced In the Middle.

When you wrote the first edition of In the Middle, in 1987, you were part of the shift in writing instruction that Don Graves showed was possible. You were among the first to ask kids to choose their own topics as writers. In the book, you described what a change this was for you, as a teacher who had worked hard to come up with creative writing assignments. You’ve referred to this transition as a period of “revolution” for teachers, as, under the influence of Graves, you showed that kids could think and act as writers. But in the second edition of In the Middle, published in 1998, you assumed a more explicit role in your classroom, writing about “teaching with a capital T.” What caused this change in your thinking? What made you become more direct in your instruction and expectations of young writers? Do you find it challenging to balance giving directions to kids with giving them responsibility to make their own decisions as writers?

The short answer is I became a parent. I don’t believe teachers have to be parents to be responsive to and responsible for their students, but for me, having been such a proponent of students’ “ownership” of their learning—of letting them make all the decisions about their writing and reading—parenthood helped me recognize the role that experienced adults play in the lives of children they care about.

Between the first and second editions, when my daughter was born and as she began to grow up, I realized that I was more interventionist as her parent-teacher than I was as a teacher in the workshop. I never withheld my knowledge from Anne. When she wanted to know how to do something, I showed her.

The word I use to describe my teaching style these days is one coined by the developmental psychologist Jerome Bruner. “Handover” describes the moments in a child’s life as a learner when an adult intervenes, demonstrates a process or strategy, and then gradually provides less assistance as the child takes over the task. As a less competent child and a more competent adult work together, the child internalizes the understandings of the grown-up.

The word I use to describe my teaching style these days is one coined by the developmental psychologist Jerome Bruner. “Handover” describes the moments in a child’s life as a learner when an adult intervenes, demonstrates a process or strategy, and then gradually provides less assistance as the child takes over the task. As a less competent child and a more competent adult work together, the child internalizes the understandings of the grown-up.

For example, when Anne was around six, I showed her how to set the dinner table. She gave it a try; then I turned the knives around, so the blades faced the plates. She tried again another night, and I praised her for mastering the conventions and folding the napkins in a fancy new way. In handover, child intentions and adult interventions are balanced.

Teachers of writing and reading workshop need to strive for this kind of balance—to show students how experienced adults do the things kids are attempting or need to know. Handover means we get to share relevant, practical knowledge with our students, and they get to put it to good use in real contexts.

The key to successful handover is knowledge. As Anne’s parent, I knew my daughter: at age six, she had been listening to read-alouds about life in the Little House on the Prairie and was ready for a “chore.” In my classroom, I have to know about—learn about—writing and reading; who seventh and eighth graders are as writers and readers; and the strengths, challenges, and intentions of each writer and reader I teach. When I act on these three kinds of knowledge, it feels healthy, productive, and respectful of every student’s potential. Handover is subtle. It’s also interesting.

I am endlessly fascinated by methods. I confess that I don’t understand a teacher who considers it a promotion to leave the classroom and assume an administrative role. For me, the authoring in air that teachers do—when I think, “Based on what I’ve learned about writing and reading, teaching them, and the student, I’ll suggest he tries that, and we’ll see what happens”—is the reason to got into education in the first place.

I value kids’ choices, ideas, and intentions. I respond to them. And I teach them. And I lead them. It’s a heady combination, one that kept me in the classroom for decades.