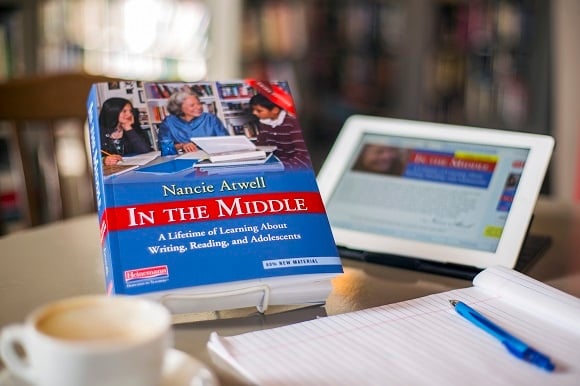

The third, updated edition of Nancie Atwell's In The Middle is out now. In a special series, Nancie blogs for Heinemann every Wednesday. In today's final post of the series, Nancie looks back on her teaching career, her beliefs, and how the work itself is her crucible.

The third, updated edition of Nancie Atwell's In The Middle is out now. In a special series, Nancie blogs for Heinemann every Wednesday. In today's final post of the series, Nancie looks back on her teaching career, her beliefs, and how the work itself is her crucible.

Over the past forty years, you’ve been a classroom teacher, a school founder and director, prolific author, national and international presenter, teacher of teachers, and sought-after consultant. You were the first classroom teacher to win the NCTE David H. Russell Award and the MLA Mina P. Shaughnessy Prize for research, and you received an honorary doctorate from the University of New Hampshire. When you reflect on your career, what stands out?

In the Middle stands out above everything. In 1984, I was an English teacher from rural Maine with an idea for a book. I knew Peter Stillman, an editor at Boynton/Cook Publishers, from our time as students at the Bread Loaf School of English. At an NCTE convention, Peter introduced me to Bob Boynton, who agreed to look at an outline and the first couple of chapters of what eventually became the first edition of In the Middle.

Bob’s suite at NCTE conventions was a setting for non-stop parties. At this one, Peter and I drank Scotch and ate chicken wings while Bob disappeared into a bedroom with my manuscript; an hour later, he emerged and offered me a contract. His confidence—his belief that a junior high teacher from the boonies had a story to tell and could write a book about it—was the beginning of my real professional life.

The 1980’s themselves are a highlight. It was a golden age of research and pedagogy in the language arts, as the old paradigms of parts-of-speech and find-the-main-idea were fractured by studies that reported on the processes of real writers and readers. The support I received from publishers, mentors, and friends—pioneers like Bob Boynton, Philippa Stratton, Dixie Goswami, Janet Emig, Donald Graves, Donald Murray, Thomas Newkirk, Glenda Bissex, Mary Ellen Giacobbe, Linda Rief, Maureen Barbieri, and Shelley Harwayne—was essential, generous, and transformative.

My school, the Center for Teaching and Learning, stands out because of its influence on the lives of so many students and teachers. For almost twenty-five years it’s been a privilege to teach and love CTL kids—to watch them grow up and recognize how they remain their essential selves as they become people who change the world.

I’m thinking of Carl and Gorän, who are helping bring their family farm into the 21st century; the nurses Annie and Catherine; Erin and Eben the environmentalists; Chloë the eco-warrior, praised in the pages of Rolling Stone by Bill McKibben; Nick, who teaches international studies at Brown and writes about nuclear proliferation and civil wars; David, who co-founded Seas of Peace and brings Israeli and Palestinian teenagers together to sail the coast of New England each summer; Joe, who came home to Maine to care for his mother after she was stricken with Alzheimer’s; Rachel the LCSW who works with elder addicts; and all the teachers, including Missy, Brenna, Molly, Ruthie, Nora, Emily, Hallie, and Anne.

Since its inception, CTL has maintained its commitment to the same mission charter schools said they were going to pursue: our faculty innovates for the good of children, and then we disseminate the methods that make a difference. So far, we've published thirteen books and DVD projects about how we teach, hosted over a thousand teachers in our classrooms through CTL’s intern program, and taught many thousands more in workshops and seminars. I’m proud of our methods, our follow-through, and our collective impact.

One roadblock to change in grades K-12 is teachers’ own experience as students. After thirteen years of schooling, it can be hard to envision new teaching structures, no matter how much we like kids and want the best for them as writers, readers, mathematicians, historians, scientists, and artists. To have created and, so far, sustained a school where teachers are charged with thinking outside of the box is a legacy I cherish.

In 2011, I was thrilled to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of New Hampshire, for over thirty years the center of my pedagogic universe. Everything I know and believe about teaching writing grows from seeds planted there by Don Graves, Don Murray, and Tom Newkirk. In real life, I only have a bachelor’s degree. Although I’ll never call myself Dr. Atwell, I did love to don a robe, march in the faculty procession, and represent the teachers who regard our work in the classroom as an intellectual enterprise.

And that’s what stands out in the end—the intellectual challenges and satisfactions of classroom teaching, the epiphanies that led to methods that nudged kids’ progress as writers and readers. I know I’ve said it before, but I love methods.

Nothing in my professional life gives me more satisfaction than figuring out how to help students do or understand something worthwhile. These practices include reading workshop itself, along with correspondence with kids about the books they've chosen; asking them to conduct booktalks and make plans as readers by maintaining lists of “someday” books; unpacking a poem together every day to introduce literary features and inspire literary writing; the power of writing off-the-page; the productive pause of the two-day walk-away; the trouble with adverbs; the rules of “so what?”, thoughts and feelings, and write about a pebble; genre studies of free verse, memoirs, reviews, essays, parodies, micro fiction, advocacy journalism, and profiles; classroom systems to manage book loans and peer writing conferences; student and teacher self-assessment as the first step in evaluation; and a school-wide Bill of Rights debated, written, and revised by students and teachers.

At its best, teaching is generative work. As the teachers of the baby-boom generation retire, I want my profession to continue to attract creative young problem-finders and problem-solvers. I’m working hard to swing the pendulum of education away from the failed vision of the market-driven “reformers” who promote technology, competition, high-stakes tests, and, in the language arts, standards that are arbitrary, grim, daunting, and utilitarian. The biggest problem with the Common Core? It denies children their childhoods and subverts the need of every student for stories, self-expression, and personal meaning.

I believe in and teach with rigor. I love young adolescents, but the work is the crucible for me. Only when the work of learning writing and reading is age-appropriate, authentic, engaging, and doable can the work of teaching them be stimulating, satisfying, productive, and doable. In a sentence, this is my vision for the next generation of English teachers.

Thus ends In The Middle Wednesdays. Please visit heinemann.com/inthemiddle to learn more about the book and read chapter previews.