By Liz Prather

By Liz Prather

Some of us will be separated by houses and streets and neighborhoods. Some of us will be separated by masks and Plexiglass and a social distance of six feet. Creating a sense of community has always been important to teachers, but this year we will have to reach out in ways that go beyond the physical proximity of bodies in a room to generate the kind of shared experience so necessary for student engagement and motivation. Community doesn’t just happen; it’s invited and built and maintained. Community as “the mental and spiritual condition of knowing that the place is shared” is built on sharing “the knowledge that people have of each other, their concern for each other, their trust in each other” (Berry 2003).

Here are six ways to do that:

See every student:

Often we are forced to look at groups of kids as data sets. This year, by virtue of smaller class size or virtual learning, we have the opportunity to work intentionally with individual students instead of pushing content out in lots of 35. Carve out a distinctive, personal connection with every kid on your roster. Inquire beyond the beginning-of-the-year interest inventory. Get curious about their passions, delights, past times. Curate one or two positive facts about every student on your roster, then capitalize on those. Be genuine in this practice as students know when a teacher fakes concern. Create an inclusive classroom that celebrates each student’s gifts, community, heritage. See each student, not as a little cog in the big wheel of your classroom, but as a unique person contributing to other unique people to form a community of learning.

Communicate often and clearly:

Specific and frequent communication reduces anxiety in students and eases parents’ minds. It also builds community: students don’t feel alone and isolated. They understand how to access information, how to contact you, and how to ask questions and look for help. Create multiple ways for students and parents to contact you; set clear expectations and boundaries around appropriate communication within specific times. Send an email every Sunday night to students and parents about what’s going to happen that week in your class. Whatever you design as a road map for learning, make these maps simple and clear, devoid of edu-speak. Name items what they are, a name that makes sense to grandma or the babysitter, not just someone with an education degree. Hand your lesson plan off to someone who is not a teacher and ask: can you understand what I’m asking you to do?

Show up as a real person:

Elementary school teachers seem to do this really well. They share stories of their pets, their families, their own childhood. (Which might explain why, when elementary teachers did drive-by parades this spring to see their students, students lost their minds like Ariana Grande just rolled up into Westgate subdivision.) While middle and high school teachers should be sensitive to the cringe factor elicited by patronizing teens, you should still show up as a real person with an identity that is more than a teacher, someone with obsessions and a history and hobbies and fears. Be vulnerable if you want students to be truth-tellers. Model grace by cutting yourself some slack if you want your students to practice the same.

Create routines:

No matter whether students and parents choose Option A, B, or C, a routine is critical for the smooth operation of both onsite and offsite classrooms. Rituals are important to a sense of belonging. Consider starting and ending your class, in the same way, every time you meet. I open with a writing prompt, spend the bulk of my class on a skill paired with practice, and end with a time to tell stories. The prompt, the skill, the practice, the stories are different every day, but those elements are always the same. These routines can be the same if you are learning face-to-face or virtually. For districts offering two options, your classroom will be effortlessly transferable from virtual to live.

Tell stories:

There’s a lot of value in just telling stories, not necessarily as a gateway to another activity or to serve another purpose. Just tell stories, share moments from your lives. In my class, we tell 7-11 stories, where the storyteller has to include seven elements in a story (place, time, character, conflict, emotion, resolution, reflection) and the audience asks eleven questions about it. In-person, storytelling might be freestyle or I might draw a subject out of a hat - pets, family, holidays, the ocean, food - and we all start telling our stories around that subject. Virtually, I might post a subject and students could share a short Flipgrid video with other students piling on the questions. Video meetings, like Zoom and Google Meeting, can help in this area also. The power of telling stories is to create a repository of shared knowledge, while the act of storytelling is a shared experience. Both build community.

Meet in groups:

Activate the four-levels of classroom connection: whole group, small group, teacher-to-student, and student-student. If you’re online, meet once a week as a whole group and once a week in small groups. Being snuggled in a smaller sub-set makes kids feel safer in the larger group. In my writing classes, I have mixed grade levels. I assign a junior or senior to serve as a mentor to a freshman or sophomore. These mentor-mentee relationships build community. The underclass students have someone to answer their questions, clarify assignments, help them with organization or work. In my virtual classes, I plan on doing the same: pair two students to serve as writing buddies, pen-pals, check-in mates. They can send an email, text, DM, Marco Polo, whatever to check up on each other.

I want to remember this: my number one goal is to treat each student in my classroom with humanity, with dignity, with respect, no matter how hectic the year becomes. Breaking down the barriers of social distancing--masks, Plexiglass, or whatever technology that stands between us--is daunting, but building a community is necessary for the engagement of your students and the efficacy of your classroom.

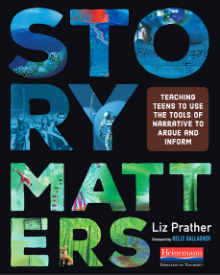

• • • Liz Prather is the author of Story Matters: Teaching Teens to Use the Tools of Narrative to Argue and Inform. Learn more about this book at Heinemann.com.

Liz Prather is the author of Story Matters: Teaching Teens to Use the Tools of Narrative to Argue and Inform. Learn more about this book at Heinemann.com.

Liz Prather is a writing teacher at the School for Creative and Performing Arts, a magnet arts program at Lafayette High School in Lexington, Kentucky. A classroom teacher with 21years of experience teaching writing at both the secondary and post-secondary level, Liz is also a professional freelance writer and holds a MFA from the University of Texas-Austin.

Liz Prather is a writing teacher at the School for Creative and Performing Arts, a magnet arts program at Lafayette High School in Lexington, Kentucky. A classroom teacher with 21years of experience teaching writing at both the secondary and post-secondary level, Liz is also a professional freelance writer and holds a MFA from the University of Texas-Austin.

Liz is the author of Project-Based Writing: Teaching Writers to Manage Time and Clarify Purpose, and Story Matters: Teaching Teens to Use the Tools of Narrative to Argue and Inform.

Berry, Wendell. "The Loss of the Future." The Long-Legged House. 2003. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press. page 61.