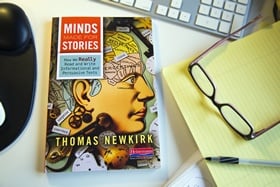

In Thomas Newkirk’s newest book, Minds Made for Stories, he challenges readers to think about narrative writing as something more: as the primary way we understand our world and ourselves. In this blog, Tom talks about his book and explains how narrative is crucial to good writing.

In Thomas Newkirk’s newest book, Minds Made for Stories, he challenges readers to think about narrative writing as something more: as the primary way we understand our world and ourselves. In this blog, Tom talks about his book and explains how narrative is crucial to good writing.

Confusion at the Core

Confusion at the Core

by Thomas Newkirk

English Department

University of New Hampshire

Durham, New Hampshire

Suppose I asked you this question: “Would you prefer fruit or dessert?”

I suspect you would blink at the logic of the question. It’s a false choice. You could have both, since they are not mutually exclusive. It is an example of what logicians call a category error.

We find a similar category error at the heart of the literacy standards of the Common Core. Texts are divided into a triumvirate—narrative, informational, and argumentative. There is a note in one appendix to the effect that “elements” of narrative are present in other forms. But that admission doesn’t remedy the problem.

This category problem also mixes aims and modes. The great rhetorician James Kinneavy would term informational an aim, as a designation of the intent of the writing. Narrative is not an aim but a mode of understanding—probably our primary means of understanding. Argumentative is the logical component of another aim—to persuade; and in my view a major flaw of the standards is the failure to embrace the more robust and comprehensive aim of persuasion.

Take a recent example—is Katherine Boo’s award-winning nonfiction book Behind the Beautiful Forevers narrative or informational? The answer is both. It’s a false choice. This three-part division creates confusion where it should create clarity.

But the greatest problem, in my view, is that it diminishes the role of narrative. It treats narrative as kind of writing, a genre, often an easier one that gives way to the more rigorous work of analysis in high school, college, and, of course, the workplace.

But we can never leave narrative behind, any more than we can shed human nature. Our very sense of identity—personal, religious, ethnic, national—is built on the stories we tell. And we lose a sense of self when, through dementia or illness, we can no longer recall these stories.

So here is my modest proposition—that narrative is the deep structure of all good sustained writing. All good writing. We struggle with writers who dispense with narrative form and simply present information (a major problem with some textbooks), because we are given no frame for comprehension. Mark Turner, a cognitive psychologist and literary critic, puts the claim this way: “Narrative imagining—story—is the fundamental instrument of thought. Rational capacities depend on it. It is our chief means of looking into the future, of predicting, of planning, of explaining.”

Narrative (or story) is central to us because of our innate need for causal explanations. We are wired to understand experience in terms of cause and effect, and stories are the best tool we have to explain causation. That is why all religions have creation myths, why all families, countries, tribes, tell stories about how they came to be. There is even evidence that individuals who know their family history (e.g., the story of the day they were born, the story of how their parents met) have a healthier sense of self.

I understand the obvious objection—what about academic writing? Surely it doesn’t fit this pattern. But as an academic writer myself, anchored in tenure, I would claim that good academic writing feels plotted—there is a tension that is resolved. There is some problem with current understanding that needs to be rectified, some itch that needs to be scratched, some reason to read on. Just creating a thesis and defending it won’t do the job.

The nonfiction writers that we read voluntarily—Malcolm Gladwell, Michael Pollan, Susan Orleans, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Stephen Johnson—all are experts at narrative writing, and they should be the models for student writing.

When we rely on stories we are often accused of being “anecdotal,” not intellectually serious. We are told that on the job and in college we do the hard stuff, the rigorous stuff; we analyze and make logical arguments. We don’t tell stories.

But we do. We can’t get away from it. Even the arguments we make are often about a version of story or in the service of story or in the form of a story (e.g., the Gettysburg Address). Scientific texts regularly describe processes (evolution, the autoimmune system, the dance of the bees, global warming, the Big Bang theory, cancer) that take narrative form.

We experience our very existence as a progression though time. We rely on stories not merely for entertainment but for explanation, meaning, self-understanding. We have “literary minds” that respond to plot, character, and arresting details in all kinds of writing.

It’s useful to remember that the word core comes from the Latin word for heart, cor. It transforms to coeur in French, corazon in Spanish. I would argue that narrative is at the heart of human identity and understanding.